Each year, the first week in October is set aside to recognize the many contributions made by the public power utilities that provide reliable electricity on a not-for-profit basis to 49 million Americans every day. As Public Power Week (Oct. 2 – 8) comes to a close, we look back on Seattle City Light’s birth, the early power struggles, and the utility’s decades-long drive to become Seattle’s provider of public power.

Seattle’s streets aglow

Seattle’s path to public power dates back to the City’s 1869 charter, authorizing the municipal government to provide lighting for the streets. But it would be several years before streetlights (powered by coal gas) brightened a handful of city streets.

It wasn’t until 1886 that an electric incandescent light bulb flickered to life for the first time in Seattle (and west of the Rocky Mountains). Current was supplied by a steam-powered generator installed by agents of Thomas Edison who soon formed the Seattle Electric Light Company (a private company unaffiliated with City Light) and won the first municipal franchise to provide electricity for lighting public streets.

Power from water

In June 1889 when the Great Fire devastated downtown, it was revealed the City’s privately owned water supplier was not up to the task. The fire made it clear that Seattle needed an abundant water source, and that the City needed to oversee its distribution. A month later, a lopsided majority of 1,851 voters to 51 authorized the City to tap the distant Cedar River. A year later, voters established a municipal water department, the first step toward developing a public utility system.

In the wake of the fire, small-scale electricity providers still marketed their services to the rebuilding city, but their rates were astronomical. In late 1895, voters approved bonds for the development of the Cedar River as a water source (hydroelectricity came later). Celebrated City Engineer R.H. Thomson took the lead on the development of the Cedar River watershed. And since Seattle would be tapping the river for its public water needs, why not build a hydroelectric plant as a source of electricity, too?

Over the next decade, technological advances allowed for electricity to travel longer distances than ever before. In 1896, voters amended the City charter to allow for the construction of a municipal lighting plant at Cedar River. But it wasn’t until the election of 1902, when Seattle voters approved the bonds needed to build the Cedar River hydroelectric facility, that the dream of public power really began to take shape.

Seattle City Light is born

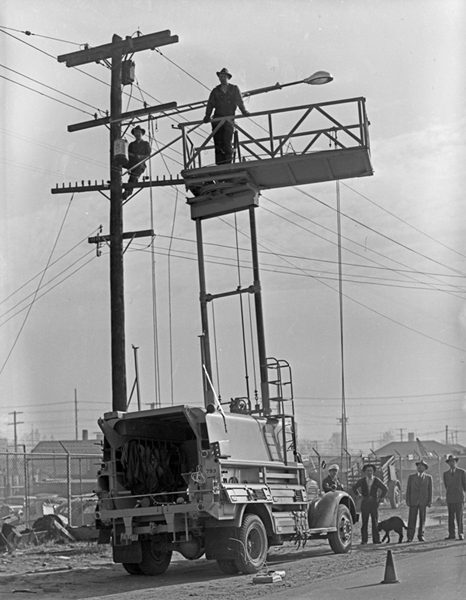

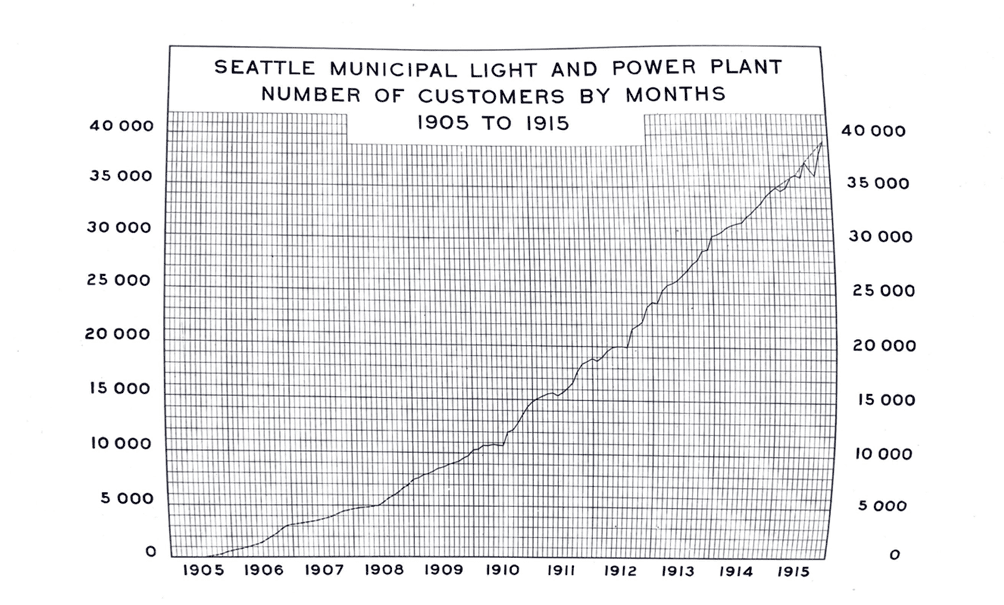

J.D. Ross, a steam engineer self-educated in the science of electricity, took over the Cedar Falls project in early 1903. On Jan. 10, 1905, the first current traveled 36 miles to a Seattle substation. Under the control of the City Water Department, the power plant began delivering public power to the streets of Seattle, increasing the demand for municipal power and forcing private power companies to cut their rates. The Water Department took possession of the private Seattle Electric Company’s street lighting system on in January 1905. The first commercial customer connected was in April 1905. By September, general applications for light and power opened to the public. The demand for power rose so dramatically that the Seattle City Council created a separate Department of Lighting – Seattle City Light in 1910.

1914-15 Biennial Report from the City of Seattle Lighting Department – Seattle Municipal Archives: Seattle Lighting Department Records (Series III) Series Identifier: 1200-03

Power struggles

The City was not the sole provider of electricity during this period; its main competitor was Seattle Electric. The private company grew in the early 1900s by buying numerous small private power companies and eventually merged with other regional power providers to become Puget Light & Power. A battle between Seattle’s public and private power providers took place over 40 years.

In 1911, Ross – Cedar Falls chief electrical engineer – was appointed to head the Department of Lighting (aka City Light). Often called the “Father of City Light,” Ross was an aggressive proponent of public power and would occupy the position for 28 years. In 1917, he obtained a federal permit to expand City Light’s hydroelectric generation capabilities by building facilities on the Skagit River – which over the ensuing decades grew to a series of three dams. On Sept. 17, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge pressed a gold key in the White House and formally started the generators for Gorge Dam (the project’s first dam) sending electricity to Seattle 100 miles away.

Ross’ victory on the Skagit in the 1920s positioned City Light as a contender for sole supplier of electricity to Seattle. In the ensuing decades, City Light and Puget Power competed economically and politically until Nov. 7, 1950, when Seattle voters approved – by a razor-thin margin – a buy-out (to the tune of $25.8 million) of the privately owned Puget Powers’ Seattle territory. Seattle finally had a unified power system under one utility. Since then, City Light has been Seattle’s exclusive electric power provider, while Puget Power – known today as Puget Sound Energy – went on to focus on powering the suburbs.

Powering the future

Today, City Light is powered by about 1,600 employees, seven hydroelectric plants and 16 major substations. The utility serves more than 426,000 residential customers, and about 51,000 commercial and industrial customers.

City Light has long been powered by creativity and innovation, and creating the utility of the future requires us to build on the successes of our past. Today, the utility’s carbon-neutral energy portfolio produces environmentally responsible, safe, low-cost, and reliable power. However, we’re in the midst of another major energy industry transition that continues to evolve along with our customers’ needs. The global shift to a lower-carbon energy system is accelerating, and public power providers are positioned to adapt to a rapidly changing energy landscape.