Seattle City Light’s more than 1,800 employees hold a bevy of positions from engineer, to lineworker, to fish biologist to fudge master (although that last one is more of a moniker). Here’s another enviable position to add to the list: archaeologist. Since assuming her role in 2016, Senior Archaeologist Andrea Weiser has played a critical role in preserving and discovering the history of City Light and the areas it affects.

Before any projects, from replacing a pole to building a large piece of infrastructure, Andrea and members of a team of consulting archaeologists research and test the area for potential historical archaeological significance that could be disturbed. Once the evaluation is complete, the utility can move forward or adjust their plans. This protocol complies with City Light’s obligations to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, as well as compliance with state and federal laws and Seattle municipal code regarding cultural resources and coordination with Tribes who retain treaty rights in their usual and accustomed areas.

While not very common, Andrea and her team may uncover an artifact that harkens back to the origins of the Skagit Hydroelectric Project’s existence. One day while conducting archaeological monitoring for a water meter project in Newhalem, a town owned and operated by City Light within the project, they made a discovery–an Old Taylor Bourbon bottle from the 1940s found nestled among the roots of a stump. The find alone was a surprise and the fact that the bottle was still intact was rare for the team to uncover.

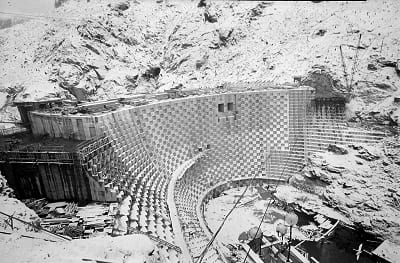

“In the 1940s, the company town of Newhalem had memorable ups and downs. At this time, Diablo and Gorge Powerhouses were in production, Ross Dam was under construction, and tourists who accessed the project by train were treated to meals and scenes that caused a buzz of excitement,” Andrea explained. “Evening activities included dances and cocktail parties. In September 1940, the Selective Training and Service Act required men between the ages of 21 and 45 to register for the draft, and in 1941, U.S. military personnel were deployed for World War II. Construction of Ross Dam was put on hold until the war ended in 1945 and Ross Dam was completed in 1949. During this era, there were many reasons to drain a bottle of bourbon.”

The team has found numerous relics of City Light’s past buried within the Project. A few years ago, while Andrea served as a consultant for the utility, her team even discovered a human-made pond buried a foot below the ground in the town of Diablo. Through historical photos and old City Light newsletters, they deduced that the pond was built between 1950 and 1955, serving as a tourist attraction in the summer for project visitors and as an ice rink in the winter for the employees and their families.

Andrea and her team have also found essential artifacts that recognize the significance of the land for native people, primarily the Upper Skagit Tribe. Before a large-scale project at the Skagit Hydroelectric Project, or for any City Light property, the utility confers with the local tribes to ensure that work doesn’t disrupt culturally-significant sites. Following one such project, City Light partnered with the Upper Skagit Tribe to create interpretive signage that recognized the importance of this land in the Tribe’s history. The sign represents a collaborative effort with the Upper Skagit Tribe to raise public awareness about ancient human history in the Skagit Project and highlight modern coordination on resource stewardship to protect and enhance fish and animal populations and habitat. Upper Skagit Tribal Council members Marilyn Scott and Edmond Mathias commemorated the sign dedication with a traditional song and honored 40 families who lived year-round in longhouses in Newhalem for generations before European settlement. Upper Skagit Tribal Policy Advisor, Scott Schuyler, spoke about a long-standing history of connections to the Skagit watershed and Newhalem, as well as treaty rights, and resources that are important to their Tribe’s culture and future.

“The council wanted to reach the public and create awareness of their history in this area,” Andrea said. “It was important to them that we recognize that the Tribe has been stewards of the land we operate in for thousands of years. We were proud to partner with them to help tell their story.”

The interpretive signage is located in Newhalem near the Skagit General Store and includes facts about how ancient archaeological evidence corroborates the oral history the Upper Skagit Tribe teaches about their connections with the area. It also consists of a polymer replica of an artifact found at the Skagit Hydroelectric Project. The original artifact, estimated to be between 4,000 and 9,000 years old, is formed from a type of stone unique to the North Cascades mountains and was recently analyzed for biological residues revealing the presence of ancient goat blood on the artifact. Which is apropos since the word Newhalem comes from the Lushootseed word “dawáylib” translates to the thread or rope used for snaring goats.

But this line of work is rife with challenges. Archaeological sites are heavily protected in Washington, and by law, all land in the state is protected from unpermitted digging in archaeological sites. Projects even on private lands that involve a lot of digging like installing a pool or septic tank, require contacting the Washington Department of Archaeology first (for more information, visit: dahp.wa.gov). When it comes to City Light projects, Weiser or other archaeologists carry out this coordination with the state and affected tribes. Because the Skagit Hydroelectric Project lies within the North Cascades National Park and Ross National Recreation Area, the archaeological sites are protected by federal law. To put it bluntly: you can’t go all Indiana Jones when you’re in the park or anywhere else. Even a trained professional archaeologist must have a permit to dig or collect artifacts.

“We do this work under federal and state laws, along with obtaining the proper permits. One of the risks of talking about archaeology is it can pique someone’s interest,” Andrea described. ” but you cannot go out and dig up areas on your own. You will be fined heavily and could even end up in jail, not to mention you could lose the trust of tribes who hold federal rights. In the state of Washington, if you knowingly disturb or dig up at a site, it’s illegal. There are also protections for keeping archeological sites, burials, and traditional cultural place locations confidential to protect them from looting and vandalism. It’s really serious stuff, especially with cultures where these areas are personally significant.”

While some people do dig or excavate without realizing the current laws, others are more nefarious. Last summer, someone had illegally dug and vandalized the Newhalem Rock Shelter archeological site near the Newhalem campground which is clearly marked as a protected site. According to a Facebook post by the National Park Service, the illegal excavation has caused “irretrievable damage” to the site and the Upper Skagit Tribe’s heritage. The Tribe is offering a $5,000 reward for information that leads to the arrest of those involved.

If you would like to learn more about archaeology in our state, The Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation’s website: dahp.wa.gov has a wealth of resources. You can also even volunteer to participate on a dig! Learn more at jobmonkey.com/parks/passport_in_time/.