Established in 1910, City Light's public power is integral to Seattle’s civic history.

Established in 1910, City Light's public power is integral to Seattle’s civic history. It’s Public Power Week. Each year, the first week in October is set aside to recognize the many contributions made by the public power utilities that provide reliable electricity on a not-for-profit basis to 49 million Americans every day. To mark the occasion, we invite you to step back in time to four pivotal periods (plot twists and all) in City Light’s history.

City Light isn’t the oldest continuously operating public utility in Washington. That honor goes to Tacoma Power, which dates to 1893. However, the utility has undoubtedly played a tremendous role in the city and the region’s growth as we know it today. Established in 1910, City Light has seen many ups and downs in its 111-year tenure, including many moments that are relatively unknown to our modern community.

Seattleites battled for decades to control their power supply

Seattle had electricity as far back as 1886, when the Seattle Electric Company lit the first incandescent lighting system west of the Rockies. In those days (and for two decades to come), power was primarily supplied to Seattle via direct current, a standard advanced by Thomas Edison. Direct current could only transmit short distances, and this limitation led to neighborhood power fiefdoms run by a ragtag collection of small companies. By 1900, the Seattle Electric Company had gobbled up most of its competitors.

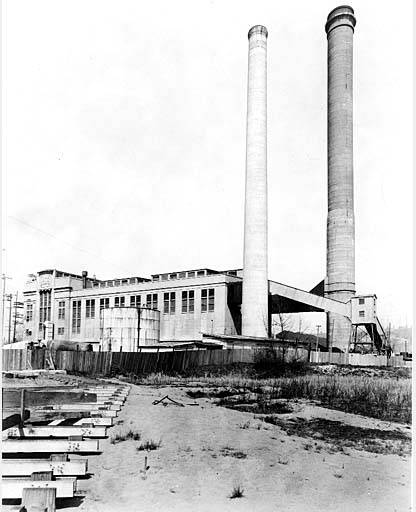

If you want to see the grandest power plant still standing from the private power era, tour the Georgetown Steam Plant — a 1906 property of the Seattle Electric Company that produced both direct and alternating current.

Luckily for the people of Seattle, the Seattle Electric Company never had a chance to become a monopoly. A publicly owned upstart called Seattle City Light outcompeted the Seattle Electric Company by providing power at lower rates, and a battle between Seattle’s public and private power providers took place over 40 years. Of course, you know the winner of that battle; in 1951, Seattle voters approved a buy-out of City Light’s privately owned competitors.

Don’t feel bad for the Seattle Electric Company, though. They went on to become Puget Sound Energy, and they are doing fine.

Public power rose from the ashes of the Great Seattle Fire

City Light’s genesis and path to competition against private utilities can be traced to one of the most pivotal events in Seattle’s history: The Great Seattle Fire.

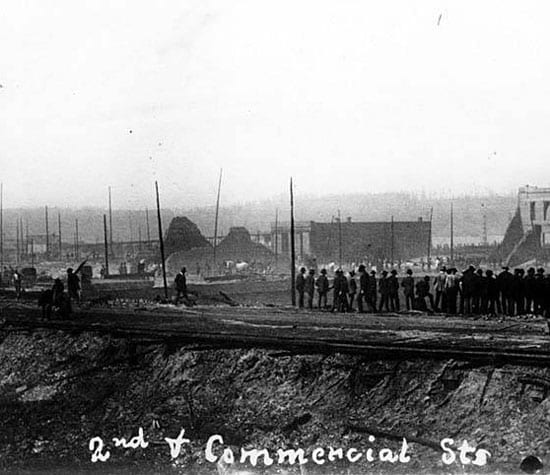

On June 6, 1889, a bubbling glue pot in a woodworking shop on Madison Avenue and Front Street (now First Avenue) overflowed. The shop caught fire. The flames spread to an adjacent liquor store and two saloons, igniting the combustible libations inside. Within two hours, the wooden buildings of Downtown Seattle were ablaze.

The City’s firefighters needed lots of water to douse the fire, but there was a major problem: Seattle’s water supply wasn’t up to the task. The private water company that piped in water from Lake Washington wasn’t pumping enough to keep up sufficient water pressure for the hoses. To add insult to injury, the water pipes themselves — made from hollowed logs — were burning as the firefighters worked. Over the next 18 hours, Seattle’s business core burned to the ground. Amazingly, there were no human fatalities.

The Great Seattle Fire made it clear that Seattle needed an abundant water source, and that the City of Seattle needed to oversee its distribution. City Engineer R.H. Thomson set his sights on the Cedar River. And since Seattle would be building on the Cedar River for its public water needs, why not build a hydroelectric plant while we were at it?

City Light was born from the Progressive Era

In the wake of the Great Seattle Fire, small-scale electricity providers still marketed their services to the rebuilding city, but their rates were astronomical. In 1890, frustrated Seattleites voted to amend the City charter to include the provision of “gas or other lights” to its inhabitants.

The growing mistrust of corporations among Seattleites compounded when the Panic of 1893 arrived, throwing the economy into a depression and closing banks around the country. The panic precipitated a progressive movement across the nation.

Voters, incensed by the actions of mighty monopolies like railroad and oil companies, were spurred into action by muckraking journalists. Issues like alcohol prohibition, labor union organization, women’s suffrage and trust-busting came to the fore as people clamored for more fairness in society. R.H. Thomson, the Seattle city engineer who had envisioned the Cedar River project, was a major civic proponent of these ideals.

The progressive movement took hold in Seattle and advanced municipal ownership of utilities. Plans to secure the Cedar River as a water source expanded to include a hydroelectric facility in 1896 when voters amended the city charter to call for its construction. But it wasn’t until the election of 1902, when Seattle voters approved the bonds needed to build the Cedar River facility, that the dream of public power began to take shape.

By mid-1904, the construction of the Cedar River facility was substantially complete. In 1905, it began delivering public power to the streets of Seattle, forcing private power companies to cut their rates.

And thus, Seattle City Light was born. Sort of.

The reason why we count 1910 as City Light’s first year (and not 1905) is that we were originally a part of the City Water Department, now known as Seattle Public Utilities. As the demand for affordable public power grew, the Seattle City Council decided to make the utility its own department in 1910.

Public power has swung elections and decided mayoral fates

Superintendent J.D. Ross, appointed to head the department in 1911, was an aggressive proponent of public power. In 1917, he obtained a permit to expand City Light’s hydroelectric generation capabilities by building facilities on the Skagit River. Electricity produced from the Skagit River reached Seattle on Sept. 14, 1924, and City Light’s boom years began in earnest.

The decades-spanning market battle between public and private power in Seattle led to all sorts of political intrigue. As construction at the Skagit Project ramped up, J.D. Ross and city leaders often clashed over budget and design issues. In January 1931, public power boosters in Seattle proposed a City charter amendment to place construction of hydroelectric projects directly under City Light’s oversight. The amendment became a referendum on the costs of public vs. private power.

Mayor Frank Edwards wasn’t a fan of public power. The day before the election, Edwards fired Ross for “inefficiency, disloyalty and willful neglect of duty.” Edwards didn’t realize that when he signed Ross’ pink slip, he was also signing his own.

The charter amendment passed, and three pro-City Light City Council members were elected to office alongside it. Public power advocates began circulating a petition for the recall of Edwards, and eventually collected an astounding 200,000 signatures — more than half of Seattle’s population at the time! Edwards was recalled in a special election on July 13, 1931, and Robert Harlin was appointed to succeed him. Mayor Harlin made the wise decision to reinstate J.D. Ross as superintendent, and Ross held that office until his death in 1939.

Public power is essential for the future of our community

As you can see, public power was an essential part of Seattle’s past, but it also has a huge role to play in the years to come. City Light’s carbon-neutral energy portfolio produces environmentally responsible, safe, low-cost, and reliable power — key traits in the fight for environmental protection and against climate change.

Our vision is to create a shared energy future by partnering with our customers to meet their energy needs in whatever way they choose. By embracing technologies like microgrids, transportation electrification, renewable energy, energy storage and distributed energy resources, we are poised for success. And when we succeed, so does our community.