March is Women’s History Month. City Light’s past includes groundbreaking women who made notable impacts on the utility sector, skilled trades, and the course of our utility. To celebrate their work, read about some influential City Light women from days gone by.

Alice Ross

If J.D. Ross was the “Father of City Light,” his wife Alice Ross was undoubtedly its mother. Even though industry generally excluded women in the first half of the 20th century, Alice was influential in crafting the public’s experience with City Light’s Skagit Hydroelectric Project

In 1924, generators at the Gorge Powerhouse sent power to Seattle for the first time. But Seattle needed more power to meet its needs. City Light needed public support for the additional dams and generators on the Skagit River, so the utility organized an enterprise now known as Skagit Tours. To entice the upper crust of Seattle into making the trip, the Skagit Project needed to become something of a fitting destination. That’s where Alice, a keen horticulturist and lover of animals, made her mark.

Alice led the development of gardens at Ladder Creek Falls, which were eventually lit with bright colors and its cultivated walking path piped with music. The Skagit Project also began hosting a zoo of sorts, with over 150 birds and animals at its peak. The first tour of the revamped Skagit Project was put on for the Women’s City Club of Seattle, an organization founded by Bertha Knight Landes, the first woman to be mayor of Seattle. You can read the itinerary of a 1929 visit from the Women’s City Club of Seattle here.

For nearly 90 years, boats have given cruises to tourists on Diablo Lake. All have been named after Alice.

Clara Fraser

As the 20th century progressed, women took on larger roles in industry. They proved themselves during wartime, and the ranks of Boeing — another major Seattle employer — were 40% female by 1943. But as men returned from war overseas, women had to organize to keep their jobs in the face of widespread sexism. Another woman with a massive impact on City Light came from that tradition of activism: Clara Fraser.

Fraser organized mothers at Boeing to take part in the 1948 Boeing Strike. Her involvement led to her firing as a Boeing assembly line electrician. Undeterred, she continued to campaign for women’s rights, against war, and against segregation throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

In 1966, Clara co-founded the Freedom Socialist Party in Seattle, splitting the Seattle branch of the Socialist Workers Party from the national organization. In 1967, she organized Radical Women, an organization that later went international and is still active today.

Mayor Wes Uhlman, who came into office in 1969, appointed former fire chief Gordon Vickery as City Light Superintendent with a mandate to increase diversity among utility staff. Vickery began to implement affirmative action programs, which led to the hiring of Clara, one of the most influential feminist organizers in Seattle.

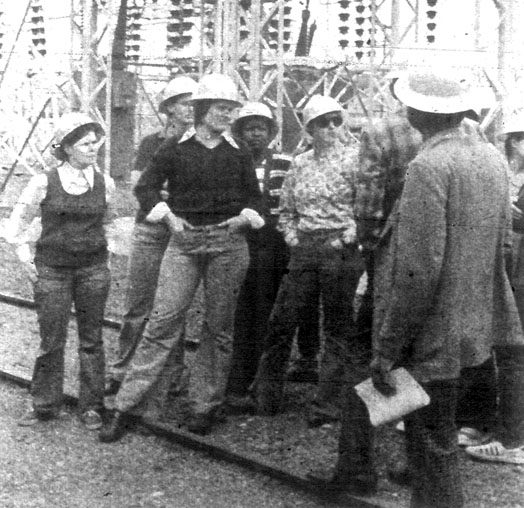

Soon after joining the utility in June 1973, Clara expanded the Electrical Trades Trainee (ETT) program, initially formed to increase the hiring of minority men, to include women. It wasn’t easy going for Clara and her allies within City Light, and her troubles compounded when she led female administrative staff to join a wildcat strike by IBEW Local 77 in April 1974. After a year of fighting to get the expanded training program off the ground, 10 women, including four racial minorities, started as trainees in June 1974.

Under Clara’s leadership, the ETT program became the first effort of its kind among any utility in the nation. The first class of women would go on to become lineworkers, substation constructors, cable splicers and electricians, but only after facing much discrimination.

In July of 1975, Clara was laid off from City Light, ostensibly due to budget cuts. She entered a seven-year legal battle against the utility and the City, eventually winning her case. In 1984, Vickery reinstated her to her job — with back pay and damages.

High Voltage Women

After a brief training period, the 10 women from the ETT program joined the City Light workforce, but they weren’t exactly welcomed. In fact, they faced overt discrimination. You can read their story in the 2019 book “High Voltage Women.”

Training for the women was inadequate, their equipment was lacking, and they weren’t initially given funds to buy appropriate clothing. When they reported to their crews, they found they were the only women on the team. They faced harassment from other crew members, and within two months of starting work in the field, six of the “high voltage women” filed complaints of sexual discrimination with Seattle’s Office of Women’s Rights and the Human Rights Department. Their grievances became a source of media and public scrutiny, and in May of 1975, most of them were given notice they would be laid off in September.

Like Fraser would later, the women of the ETT program fought their layoffs. The Office of Women’s Rights found that their discrimination complaints were merited, and in August of 1976, Mayor Uhlman ordered Superintendent Vickery to reinstate them to their jobs.

Robin Calhoun

In 1976, City Light turned away from building nuclear generation facilities and towards conservation to address Seattle’s energy needs. With the help of private citizens and public officials, City Light authored a report called “Energy 1990” that detailed how energy conservation would make nuclear production unnecessary.

While producing the report, Chief Engineer Robert Sheehan met and aggressively recruited environmental consultant Robin Calhoun to head up City Light’s emerging conservation efforts. When Robin started, she found no funding for a conservation program. In fact, conservation programs at electric utilities were unheard of at the time.

Robin quickly proved her mettle at advancing the utility’s conservation goals in the face of adversity. She only had two full-time direct reports, so she marshaled City Light staff from many departments to work on the project. After drawing out a proposal for a grant, she went to the U.S. Department of Energy and convinced the agency to provide almost $2 million in support.

Superintendent Vickery, who had been a supporter of the nuclear option, embraced the conservation effort. With the help of a public engagement campaign, City Light launched one of the first utility conservation campaigns in the nation, and it became a model nationwide.

In this video, Robin recounts the launch of City Light’s groundbreaking conservation program and talks about working conditions for women and racial minorities at the time. Her remarks begin 33 minutes in.

Roberta Palm Bradley

City Light’s workforce made great strides towards integration in the 1980s, and in July of 1992 a woman got the top job. Mayor Norm Rice appointed Roberta Palm Bradley to be superintendent, and she became the first woman and first African-American to head a major municipal public utility in the country.

While Bradley’s hiring showed how much progress women had made in the workplace, she also had to contend with City Light’s legacy of past discrimination. She faced budgetary challenges and quickly announced staff reductions in the hundreds, which alarmed union leaders and the workforce. She did succeed in putting the utility on a budgetary diet to the tune of $10 million, was praised for some internal measures such as employee selection of supervisors and was credited for helping usher the utility into an era of competition and deregulation.

But staff morale was low and discrimination complaints kept coming in. Roberta, who had been a division director at Pacific Gas & Electric in California, was an outsider both geographically and culturally. Her experience, developed at a private utility, didn’t prepare her for Seattle’s slower, process-heavy way of doing things. In August 1994, Roberta resigned from her position. Many maintained she was forced out. A 1994 Seattle Times article recounted the words she said she told the mayor upon her resignation: “I am the right person for this job, but I am the wrong person for this culture.”